The sciences may explain how the universe works, however it is the arts that define our relationship with it.

The latest Education Matters column is now available on the newly redesigned Mercury online magazine! Read it here.

The sciences may explain how the universe works, however it is the arts that define our relationship with it.

The latest Education Matters column is now available on the newly redesigned Mercury online magazine! Read it here.

Looking up in awe at the night sky, the stars and planets pop out as bright points against a dark background. All of the stars that we see are nearby, within our own Milky Way Galaxy. And while the amount of stars visible from a dark sky location seems immense, the actual number is measurable only in the thousands. But what lies between the stars and why can’t we see it? Both the Hubble telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have revealed that what appears as a dark background, even in our backyard telescopes, is populated with as many galaxies as there are stars in the Milky Way.

So, why is the night sky dark and not blazing with the light of all those distant galaxies? Much like looking into a dense forest where every line of sight has a tree, every direction we look in the sky has billions of stars with no vacant spots. Many philosophers and astronomers have considered this paradox. However, it has taken the name of Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers, an early 19th century German astronomer. Basically, Olbers Paradox asks why the night sky is dark if the Universe is infinitely old and static – there should be stars everywhere. The observable phenomenon of a dark sky leads us directly into the debate about the very nature of the Universe – is it eternal and static, or is it dynamic and evolving?

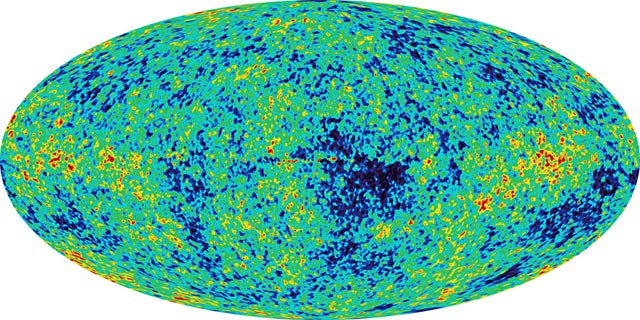

It was not until the 1960s with the discovery of the Cosmic Microwave Background that the debate was finally settled, though various lines of evidence for an evolving universe had built up over the previous half century. The equations of Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity suggested a dynamic universe, not eternal and unchanging as previously thought. Edwin Hubble used the cosmic distance ladder discovered by Henrietta Swan Leavitt to show that distant galaxies are moving away from us – and the greater the distance, the faster they’re moving away. Along with other evidence, this lead to the recognition of an evolving Universe.

The paradox has since been resolved, now that we understand that the Universe has a finite age and size, with the speed of light having a definite value. Here’s what’s happening – due to the expansion of the Universe, the light from the oldest, most distant galaxies is shifted towards the longer wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum. So the farther an object is from us, the redder it appears. The JWST is designed to detect light from distant objects in infrared light, beyond the visible spectrum. Other telescopes detect light at still longer wavelengths, where it is stretched into the radio and microwave portions of the spectrum. The farther back we look, the more things are shifted out of the visible, past the infrared, and all the way into the microwave wavelengths. If our eyes could see microwaves, we would behold a sky blazing with the light of the hot, young Universe – the Cosmic Microwave Background.

The next time you look up at the stars at night, turn your attention to the darkness between the stars, and ponder how you are seeing the result of a dynamic, evolving Universe.

A version of this post appeared in the NASA Night Sky Network‘s monthly Night Sky Notes for September 2023.

We are familiar with many types of shadows, but two of the most rare and exciting relate to the Moon’s and Earth’s shadows.

Remember back to your first eclipse, that moment when you stood in the Moon’s shadow. What was the experience like? How did you respond to the awesome spectacle in the sky? Did someone help you understand what was happening, or did they just tell you? How have you mentored others to come to a deep understanding of eclipses, taking care to not reinforce any lingering preconceptions? Or reduce their visceral experience to a set of facts and figures? Drawings and words only go so far in promoting deeper understanding so people have a true internal model of what is taking place, of the lunar shadow. The use of modeling tools and direct experience with their manipulation can help people’s cognitive

understanding, complementing the awe and wonder they feel when experiencing the actual phenomenon. It all starts with the basics, a source of light, and an object to block the light.

We are all sources of illumination to foster deeper understanding, the trick is to not eclipse the experience with our own preconceptions.

An explanation of a shadow is something we generally think of as intuitive. It turns out shadows, particularly when it comes to those large-scale ones celestial objects produce, are not as intuitive as we might think. Shadows make their appearance in classrooms very early on, and the subject forms the basis for two Astronomical Society of the Pacific research projects with preschoolers and first graders. In both projects, learners used a flashlight and a figure of a bear to create shadows, changing their characteristics such as length and direction depending on the position of the light. First grade students also went outside to track the changing pattern of shadows with the actual Sun. Basically, they learned the creation of a shadow requires a light source, and an object to block the light. So far this is fairly basic and intuitive.

Scaling the aforementioned activities up to larger objects starts to create challenges for learners, even those who left their school days far behind. Walking through a city it is relatively easy to recognize there is a “shady side of the street” with buildings blocking the sunlight from reaching the sidewalk. This provides a pleasant, cooler place to walk on a hot day. Or we put up an umbrella to create shade (in this case another word for shadow) in our backyards. People may even have an understanding of the shadows mountains create, and how climbing to the top allows them to see one side in sunlight and the other in shadow. In all these cases, the shadows still have a lot of ambient light illuminating the scene. Cases where an object blocks enough light to create darkness might include closing a door to someone’s room at night, the darkness under the bed, or a house with blackout curtains even when the Sun is shining brightly.

Scaling our objects still larger to the size of planets starts to create misconceptions about shadows. On a dark evening, think about how someone might respond if you ask them to explain why it is night. Would they say it is dark out because we are in the shadow of Earth? A few might say it is dark because we are in the shadow of the Moon. The latter case was actually mentioned in an article on npr.org. (The workers in the NPR story were pouring concrete in the shadow of Earth, not the Moon as was reported.)

And what about the changing lunar phases? How do people explain those? A relatively common answer is the darkened parts of the Moon are due to the shadow of Earth. Going back to shadow basics and the need for a light source and something to block the light, we can demonstrate with simple materials the light source is the Sun, and the object blocking the light in the case of nighttime is Earth, or the Moon itself in the case of its phases.

Eclipses = shadows

The question might arise: Do we ever experience the shadow of the Moon, or does the shadow of Earth ever encompass the Moon? The answer in both cases is a resounding YES!

While we can stand in the shadow of Earth 365 days per year, the Moon only passes through or touches it between two and four times per year during a Full Moon. At those times, if we are on the nighttime side of Earth, we share the experience of Earth’s shadow with the Moon. Thus, many people can experience seeing the shade of Earth encompass the Moon. (This is known as a lunar eclipse.)

The experience of standing in the shadow of the Moon is much rarer, partially due to the smaller size of the shadow. While the Moon will either completely or partially block light from the Sun at least twice, and up to five times, per year, fewer people are able to have a direct experience of the Moon’s shadow.

The total solar eclipse of August 21, 2017, was probably the most accessible eclipse for the people in North America. While standing in the total shadow of the Moon is limited to a narrow band, even many people unable to travel to the path of totality were able to see a partial eclipse. Unlike lunar phases, which are due to the Moon’s changing position as it orbits Earth, a partial eclipse is where the Moon only partially obscures the Sun. A great many people experienced an eclipse for the first time, and there

was a concerted effort to help them understand what it was they observed.

The two solar eclipses taking place within the space of six months (an annular in October 2023 and a total in April 2024) are opportunities to recapture the excitement from 2017, and bring the awe and wonder to whole new audiences. Even a partial eclipse has us standing in the shadow of the Moon.

A version of this post originally appeared in Mercury Magazine, a publication of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific.

A post with the same title appeared in September 2017. It tells about the author’s experience leading up to, and on the day of the August 21, 2017 total solar eclipse.

Humans have a vast ability to notice visual cues and patterns

Recently I saw a video showing a room that slowly morphed from one arrangement and decor to another over the course of a minute or two. The change happened so slowly I was barely aware there were any changes. It reminded me of the video educators show to demonstrate perception where viewers are asked to count the number of times one team passes a basketball. Meanwhile a person in a gorilla suit walks into the midst of the two teams, beats its chest, then leaves. Most people don’t notice the gorilla until it is pointed out to them on a second viewing. These two videos may demonstrate how many things happen too slowly, or how we are focused on one aspect too intently to notice change happening right in front of us.

It’s not through lack of experience of looking for changes in the visual pattern; we are, after all, visually oriented creatures. From the time we are born, we observe the patterns around us and associate certain shapes, such as a bottle, with fulfillment of needs. Gradually we start to associate certain sounds with those visuals, and still later the set of visual markings we call text with the former sounds and visuals. And, we are trained to notice these changes from a young age. “Spot the Difference” puzzles are commonly found in newspapers and magazines. I fondly recall Highlights Magazine and looking to find the hidden objects in pictures. Or searching for Waldo in a sea of people. Some areas of astronomy have a similar investigative approach, comparing images of the same scene captured at different times. This was the method used to discover new Solar System objects, most notably Pluto. We now have computers and advanced software to do this for us.

The ability to pick out changes, to use these visual cues without relying on software to detect them, is something we as educators should encourage more often. However, a common way we engage people in education is to provide the language for a phenomenon before allowing learners the opportunity to experience it on their own. In essence, we provide the model explaining what something is rather than having the learner discover their own. This is particularly noted when there are predetermined outcomes to an investigation or when students are engaged in confirmation activities. Allowing learners to explore first before applying language does take longer, however it takes advantage of their innate curiosity and ability to notice. Similarly, when we carry out outreach events we as educators have a tendency to tell people what they are looking at in detail before they have a chance to see it for themselves. It’s akin to providing the answers to the above-mentioned puzzles without offering the challenge for people to discover them on their own.

Another option is to give people a couple facts about a phenomenon without additional explanation, then observe and listen for signs of wonder and curiosity. This type of interaction promotes thought on the part of the audience even though they were provided some of the initial language associated with the phenomenon and usually elicits questions about what they hear or notice. In formal education, this process/method is generally referred to as guided inquiry, with the teacher acting as facilitator for student investigations. Learners have the opportunity to experience a phenomenon and then ask questions for their own investigations.

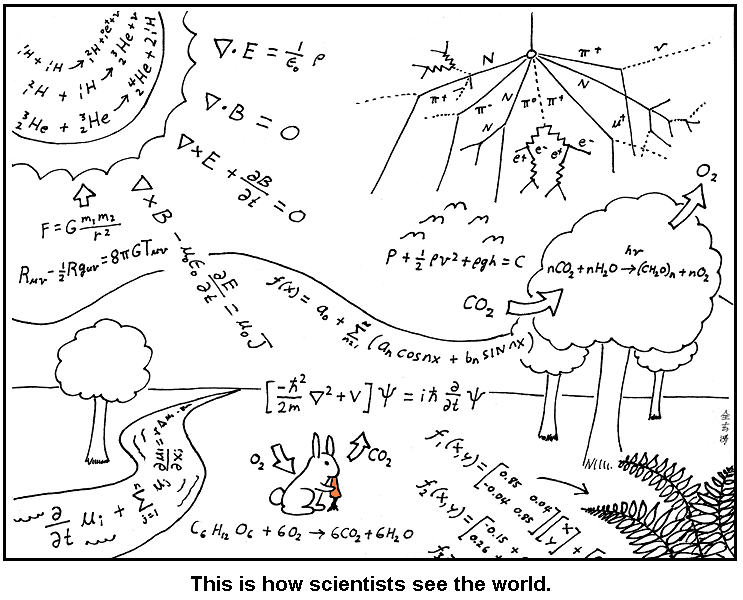

It isn’t difficult to find a phenomenon to observe and investigate; they are all around us and waiting for us to notice. One of my favorite cartoons I show to participants in my workshops demonstrates this.

Some might take issue with the idea of “unweaving the rainbow,” and comment it detracts from awe and wonder at the natural world. But for those of us in the sciences, knowing there are noticeable patterns all around us enhances our wonder and curiosity. We seek to understand how the universe works. Knowing there are patterns – and with a little work we can decipher them – promotes curiosity and the excitement of discovery. And it’s only a small step to bring learners of all ages along as we seek to reveal these patterns.

After all, we all have had lots of practice with this, while growing up: noticing and building our own models to explain the world we find ourselves immersed in.

This post originally appeared in the Summer 2022 issue of Mercury Magazine, a publication of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific

A site to discuss better education for all

Musings on the condition of our planet Earth, its place in the cosmos, and the thoughts and state of mind of its inhabitants.

Writing and photos about whatever strikes my fancy

Science, Society, and Fiction from Matthew R Francis

... is another astronomer's data

Musings on the condition of our planet Earth, its place in the cosmos, and the thoughts and state of mind of its inhabitants.

Walking alongside Opportunity as she explores Endeavour...

Traipsing the world in the name of astronomy

A Blog by Linda Shore

Musings on the condition of our planet Earth, its place in the cosmos, and the thoughts and state of mind of its inhabitants.

The latest news on WordPress.com and the WordPress community.