Looking up in awe at the night sky, the stars and planets pop out as bright points against a dark background. All of the stars that we see are nearby, within our own Milky Way Galaxy. And while the amount of stars visible from a dark sky location seems immense, the actual number is measurable only in the thousands. But what lies between the stars and why can’t we see it? Both the Hubble telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have revealed that what appears as a dark background, even in our backyard telescopes, is populated with as many galaxies as there are stars in the Milky Way.

So, why is the night sky dark and not blazing with the light of all those distant galaxies? Much like looking into a dense forest where every line of sight has a tree, every direction we look in the sky has billions of stars with no vacant spots. Many philosophers and astronomers have considered this paradox. However, it has taken the name of Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers, an early 19th century German astronomer. Basically, Olbers Paradox asks why the night sky is dark if the Universe is infinitely old and static – there should be stars everywhere. The observable phenomenon of a dark sky leads us directly into the debate about the very nature of the Universe – is it eternal and static, or is it dynamic and evolving?

It was not until the 1960s with the discovery of the Cosmic Microwave Background that the debate was finally settled, though various lines of evidence for an evolving universe had built up over the previous half century. The equations of Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity suggested a dynamic universe, not eternal and unchanging as previously thought. Edwin Hubble used the cosmic distance ladder discovered by Henrietta Swan Leavitt to show that distant galaxies are moving away from us – and the greater the distance, the faster they’re moving away. Along with other evidence, this lead to the recognition of an evolving Universe.

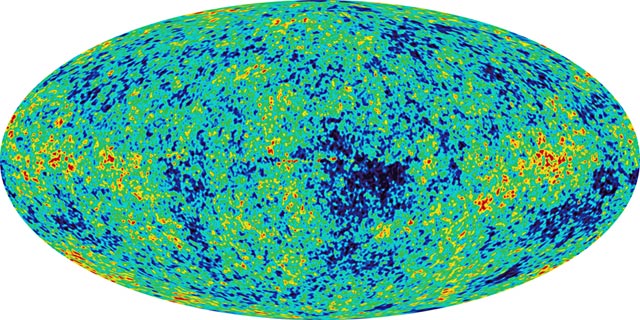

The paradox has since been resolved, now that we understand that the Universe has a finite age and size, with the speed of light having a definite value. Here’s what’s happening – due to the expansion of the Universe, the light from the oldest, most distant galaxies is shifted towards the longer wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum. So the farther an object is from us, the redder it appears. The JWST is designed to detect light from distant objects in infrared light, beyond the visible spectrum. Other telescopes detect light at still longer wavelengths, where it is stretched into the radio and microwave portions of the spectrum. The farther back we look, the more things are shifted out of the visible, past the infrared, and all the way into the microwave wavelengths. If our eyes could see microwaves, we would behold a sky blazing with the light of the hot, young Universe – the Cosmic Microwave Background.

Image credit: WMAP Science Team, NASA

The next time you look up at the stars at night, turn your attention to the darkness between the stars, and ponder how you are seeing the result of a dynamic, evolving Universe.

A version of this post appeared in the NASA Night Sky Network‘s monthly Night Sky Notes for September 2023.

Nice explanation for resolving the paradox, connecting it to the CMBR and pointing out that were we to have been able to see in the microwave spectrum, there would never have been a paradox at all! Though we would have wondered why the CMBR was so cold whereas the visible stars are so hot.

Einstein’s GTR (in the original form without the Cosmological Constant) simply does not have a steady state solution. With the CC, there is a steady state solution, but it is unstable and requires essentially infinite fine-tuning.

Theoretical attempts to modify GTR to allow for a steady state solution (e.g. Hoyle-Narlikar) have been increasingly convoluted (“stars generate iron needles”) and appear desperate in their attempt to preserve the wish for a steady state universe. Theory aside, the researchers ignore overwhelming evidence for a dynamic universe.

LikeLike